Connecting home care

The missing link

Few would challenge the relevance of home care to a sustainable health care system. And yet with the “rescue, repair, and return” approach underpinning acute care in Canada, the broader system has generally been slow to recognize and build an operating system that links to home and community care.

The home and community system is comprised of thousands of organizations providing care and support to people at home. Incorporating the community network into the broader health care system has been limited by policy and a long history of facility-based orientation. In Ontario, the Personal Health Information Protection Act (PHIPA) modernization[1], 2022, means that home care service provider and community organizations can now be considered health information custodians (HICs)[2]. This change positions home care for bi-directional information exchange with the provincial digital assets which includes drug repository, immunization repository, lab results, diagnostic imaging, and the acute and community clinical data repository (CDR). This is a crucial accomplishment which needs to be leveraged to achieve better patient care in Ontario. While promising, there are still several hurdles for the system to overcome to ensure home and community care service provider organizations and their frontline staff are connected.

“Axe the fax”

Most recently the Ontario government made it official – faxes in healthcare in Ontario will be replaced by other digital communication alternatives within five years.[3] In other words, get connected or be left by the wayside. It is perhaps this kind of unifying action that will get the job done. As we saw during the COVID-19 pandemic, where there is a will and intense collaboration, fast mobilization can be achieved.[4]

Building a Home and Community Care Digital Architecture

All members in the patient’s “circle of care” must be connected, able to communicate, collaborate, and coordinate care regardless of funding source or place of care. Canadians expect their health information to be digitized and accessible across the healthcare ecosystem, including at home.

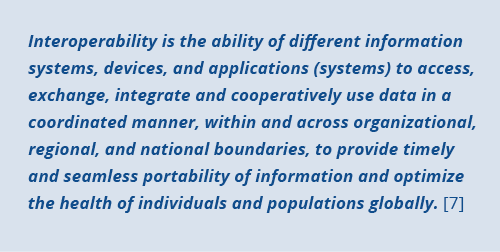

Ontario’s strategic declaration reinforces the need for establishing a new home and community care digital architecture[5] that supports home and community care frontline service providers and is built on specifications that allow connection without multiple point-to-point integrations[6] to communicate with various providers or across various regions. A variety of digital health systems is inevitable and arguably important to respond to various constituency groups across the province and potentially the country. The unifying element is the interoperability framework with open and securely accessible application programming interface (API) that underpins and enables information exchange. The use of interoperability standards and terminologies and population-specific minimum data sets can lead to better communication, improved patient outcomes, and more efficient care delivery. They can enable seamless bi-directional sharing of information amongst providers and support the rapid adoption of solutions such as virtual care, and remote monitoring.

Sharing information between systems (interoperability) requires several components to come together to ensure digital health systems are all speaking the same language and can connect. These include:

• One Single Provincial Gateway: An agreed upon solution for achieving that acts as a central connection enabling secure and efficient data exchange data.

• FHIR based Standards and Technical Specifications: The integration of common standards and terminologies which define the rules, protocols, and formats for exchanging data, and ensure that all systems speak the same language.

• Infrastructure: Hardware components such as servers, routers, and switches, as well as software components such as middleware, APIs, and data integration tools to support the exchange of information between different systems.

• Data Governance: Establishment of policies, procedures, and guidelines that govern the exchange of data and the use of common standards ensuring data that is accurate, complete, and consistent across different systems.

• Security: Protection against unauthorized access, hacking, and other security threats.

• Patient Relevance: Architecture designed with relevant patient Use Cases.

• User Acceptance: Users must be willing and able to use the systems and standards that enable interoperability for it to be successful.

Together, these create a scalable framework by which many applications can communicate, which in the long term, saves time, money and mitigates risk.

“Catch the fire”

In recent years, the international HL7® Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources or FHIR®, pronounced ‘fire’, standard has been adopted by many organizations and jurisdictions as part of their digital architecture approach. The standard describes data formats and elements as well as API for the exchange of Electronic Health Records.

The priority is to align on a common digital architecture that allows home care to ‘plug and play’ into provincial health systems and to optimize real time bi-directional information exchange.

It’s the patient’s record…

A commitment to one record, the patient’s record, across the healthcare system can have a significant impact on care, quality improvement, research, and financial management. This record is a comprehensive history of a patient’s health information and is typically maintained by the health care provider who is responsible for the patient’s care. With more health care in the community and the technology to enable that care, home and community care must be included as a contributor and have access to the record.

A further paradigm shift – beyond provider as the health information custodian, to a system where the patient has access and ownership of their health record – must occur. Home care providers can help ensure this record is complete and enhances care where Canadians want it, in their home.

At the end of the day, health care is enabled by technology. It is essential to the future of health care, meeting expectations and supporting practitioners to give their best.[8] To be the future of health care, home care must be connected.

References

- Kosseim, P., Di Re, M. (2020, September 22) Recent PHIPA Amendments and Privacy/Security Considerations for Virtual Care. Information and Privacy Commissioner of Ontario. Presentation. Retrieved Feb 21, 2023 from https://www.ipc.on.ca/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/2020-09-22-alliance-for-healthier-communities.pdf

- Prior to this time home care providers were agents of the HIC (Home and Community Care Support Services) and could not have access to any of the digital assets.

- Government of Ontario. (2023 February 08) Your Health: A Plan for Connected and Convenient Care. Retrieved Feb 21, 2023 from https://www.ontario.ca/page/your-health-plan-connected-and-convenient-care?utm_source=newsroom&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=%2Fen%2Frelease%2F1002683%2Fyour-health-a-plan-for-connected-and-convenient-care&utm_term=public

- Isaackz, S. (2022, November 21) Bridging the Digital Divide in Community – Lessons from the pandemic. Retrieved Feb 21, 2023 from https://cdnhomecare.ca/bridging-the-digital-divide-in-community-lessons-from-the-pandemic/

- Technology architecture manages the structure and interaction of platform services with logical and physical technology components.

- Point-to-point integration is a type of integration where a direct connection is established between the two software applications. However, the approach lacks flexibility and scalability and can limit the ability of the organization to adapt to changing business needs or technology trends.

- HIMSS. Interoperability in Healthcare. Retrieved Feb 21, 2023 from https://www.himss.org/resources/interoperability-healthcare

- Beltzner, C. (2022, November 8) Technology is the enabler. Retrieved Feb 21, 2023 from https://cdnhomecare.ca/technology-is-the-enabler/